Edge Container Registries Explained: How to Distribute Images Reliably at Scale

A mostly hidden piece of the container application puzzle is the image registry. If you’ve used Linux containers, you’ve come across one: it’s where container images are stored. Registries can be public (like Docker Hub) or private, typically where you store the output from your CI/CD pipeline.

When deploying an application to a container runtime, the first step is always to fetch the container images from a registry. In a cloud environment, this step usually gets glossed over quickly because it “just works.” Your registry is part of your cloud provider’s offering, running in the same data center, with fast and reliable connectivity. Your pipeline pushes images there, your workloads pull from there, and you don’t think much about it.

But at the edge? That’s a different story.

Edge environments break several assumptions that cloud-based applications take for granted. You might be deploying to hundreds or thousands of sites instead of a handful of clusters. The connectivity to those sites might be slow, unreliable, or expensive, not a fat pipe within a data center. A site might have multiple hosts that all need the same images. And you really don’t want to manage yet another piece of infrastructure at every location.

So how do you get container images to all those places, reliably and efficiently?

In this post, I’ll walk through what a container image actually contains, what can go wrong when distributing images at the edge, and how Avassa’s built-in registry handles all of it for you, so you don’t have to think about it.

Read more: What Are Containers? A Complete Guide to Software and Application Containers

Manifests and blobs: the building blocks of OCI container registries

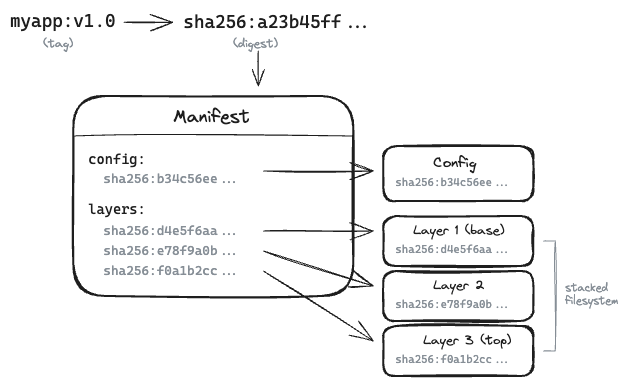

A container image consists of a manifest and one or more blobs. The manifest is essentially a list of contents: it describes what’s in the image and references each piece by its digest, a cryptographic hash of its contents. The blobs are the actual data, typically layers, which are compressed archives of files that stack on top of each other to form the final filesystem your container will see.

When you build an image, each instruction in your Dockerfile (or equivalent) can create a new layer. Because everything is content-addressed (identified by that hash) you get two nice properties for free. First, integrity: if the content doesn’t match the digest, you know something is wrong. Second, deduplication: if two images share the same base layer, that layer only needs to be stored (and transferred) once. This is a significant efficiency gain, especially when you have many images built on common foundations like alpine or ubuntu.

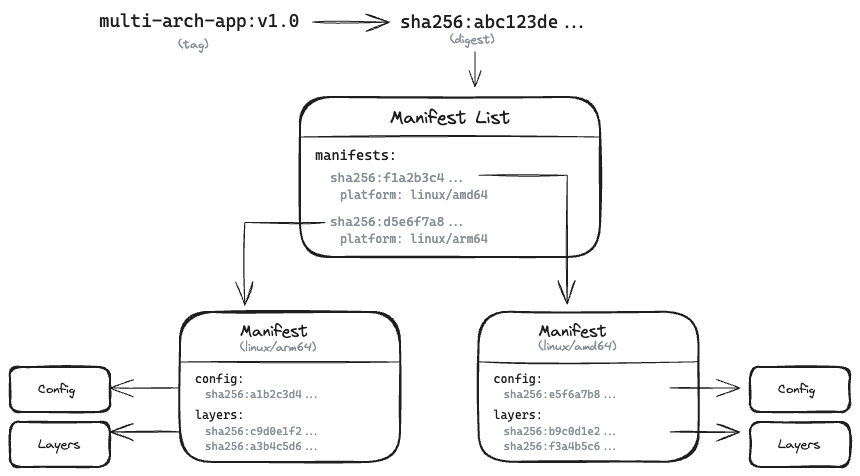

For images that need to run on multiple CPU architectures (say, both amd64 and arm64), there’s an additional level of indirection: an image index (sometimes called a manifest list). This is a manifest that points to other manifests, one per platform. When you pull such an image, the client automatically picks the right one for the host it’s running on.

A registry is simply where these manifests and blobs are stored and served from. The client (Docker, Podman, containerd, etc.) talks to the registry over HTTP to fetch manifests and then pull the individual layers. All of this is standardized in the OCI Distribution Specification, which means registries and clients from different vendors can interoperate.

Under the hood, everything in a registry is stored as a blob: the manifest, the config, and the layers are all just blobs identified by their digest. What distinguishes them is their media type (sometimes called MIME type): the manifest has one media type, the config another, and layers yet another. The registry doesn’t really care what’s inside; it just stores bytes and serves them back when you ask for a particular digest. This simplicity is what makes the system so robust and interoperable.

The edge problem: distributing container images at scale

In a cloud environment, image distribution is a solved problem. Your registry lives in the same datacenter as your workloads, bandwidth is plentiful, and the network is reliable. But move to the edge and those assumptions fall apart.

Scale changes everything. Instead of deploying to a handful of clusters, you might be distributing images to hundreds or thousands of sites: retail stores, factory floors, hospital wards, cell towers. Each site needs to pull images, and doing that efficiently at scale requires more than just “point everyone at the central registry.”

Connectivity is unreliable. Edge sites often connect over links that are slow, expensive, or intermittent. A download that gets interrupted halfway through shouldn’t mean starting over from scratch. You want to resume where you left off, ideally at the byte level within a layer, not just at the layer level. And if your site loses connectivity for a few hours (or days), it shouldn’t stop your applications from running.

Resources are constrained. Edge nodes typically aren’t beefy servers with terabytes of storage. You need to be smart about what images are stored locally, clean up images that are no longer needed, and avoid duplicating data unnecessarily.

Sites often have multiple hosts. A site might be a small cluster of machines sharing a single uplink. If three hosts all need the same image, you really don’t want each of them pulling it independently from the central registry. That’s three times the bandwidth for no good reason.

Tags can lie. In the container world, a tag like myapp:latest can point to different image digests at different times. If you deploy an application across many sites over the course of a few hours, and someone pushes a new version mid-rollout, you could end up with different sites running different code, all thinking they’re running the same tag. That’s a debugging nightmare waiting to happen.

Security can’t be an afterthought. Image pulls need to happen over encrypted connections, and sites need to authenticate properly with the central registry. If a site is compromised, you need a way to cut it off: no more image pulls until the situation is resolved (in the Avassa Edge Platform, this is what the site quarantine feature does). Managing certificates and credentials across hundreds of sites is its own operational burden.

All of these issues are solvable, of course. You could set up caching proxies at each site. You could write scripts to pre-pull images. You could pin digests manually in your deployment specs. You could manage TLS certificates and authentication tokens across your fleet. But now you’re building and maintaining infrastructure instead of running your applications.

The Avassa approach: built-in registries at both ends

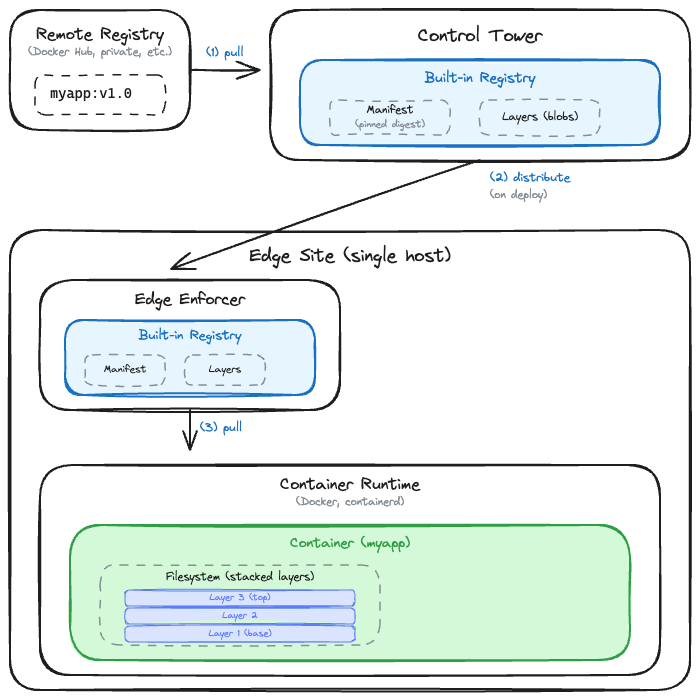

The Avassa Edge Platform includes a container registry at both layers of the architecture: one in the Control Tower (the central management plane) and one at each edge site, built into the Edge Enforcer. This isn’t an optional add-on; it’s a core part of how the Avassa Edge Platform works.

How container images flow to edge sites

When you define an application in the Avassa Edge Platform, you specify container images just like you would anywhere else: by name and tag, pointing to whatever remote registry hosts them (Docker Hub, your private registry, etc.). When you save that application specification, the Control Tower automatically pulls those images from the remote registry and stores them in its own built-in registry. This happens in the background; you don’t have to do anything.

When you deploy the application to sites, the images are distributed from the Control Tower to those sites. For multi-host sites, the Edge Enforcer first selects which host will be responsible for fetching each image, ensuring the download work is distributed sensibly across the cluster. That host then checks what it actually needs: it fetches the manifest, selects the right architecture for the site’s hardware, and identifies which blobs aren’t already present locally. Only the missing pieces get downloaded.

Once all the required images are fully downloaded and replicated within the site, the application is allowed to start. This means you never end up with a half-deployed application waiting for an image that didn’t make it.

Digest pinning: no more “tags can lie”

The moment you create a deployment, the Control Tower resolves each image tag to its current digest. From that point on, every site receives that exact digest, not the tag. Even if someone pushes a new version to the original registry mid-rollout, your deployment stays consistent. All sites run the same code, guaranteed.

Dealing with flaky connections

Edge sites won’t always have reliable connectivity, and the Avassa registry is designed for that reality. If a download gets interrupted, whether at the layer level or partway through a single blob, the Edge Enforcer picks up where it left off. Downloads resume from the last byte received, not from the beginning of the layer or the beginning of the image. No wasted bandwidth, no starting over.

And once images are on-site, they stay there. If connectivity to the Control Tower drops for hours or days, your applications keep running. The site operates autonomously until the connection is restored.

Efficient use of bandwidth and storage

Like any OCI-compliant registry, the Avassa registry benefits from content-addressable storage: shared layers are only transferred and stored once. But there’s more to it than that.

In a multi-host site (a small cluster of edge nodes sharing a single uplink), images are pulled once from the Control Tower and then replicated locally among the hosts. Each blob is replicated to a subset of hosts in the cluster, while manifests are always copied to every host. This means any host can serve an image pull request without reaching back to the Control Tower, while still being economical with storage. If a host goes down, the remaining hosts still have what they need.

On the cleanup side, the site registry automatically removes images that are no longer needed by any deployment. When an application is updated or deleted, the registry garbage-collects the blobs that are no longer referenced. You don’t have to worry about edge nodes filling up with stale images over time.

Security without the overhead

All image transfers happen over HTTPS, and each site authenticates to the Control Tower using a site-specific token. You don’t have to manage certificates or credentials at the site level; the platform handles it.

If a site is compromised, the quarantine feature lets you cut it off immediately. A quarantined site can’t pull new images (or receive new deployments) until you explicitly restore it.

Why not just use Docker’s cache?

You might wonder: if Docker already caches images locally, why do we need a separate site registry? A few reasons:

- Docker’s cache is per-host, not shared across a cluster. If you have multiple hosts at a site, each one pulls independently.

- There’s no central visibility into what’s cached where, and no automatic cleanup tied to your actual deployments.

- Most importantly, edge sites are often locked down. Outbound network access is restricted, and hosts can’t just reach out to arbitrary registries on the internet.

The Avassa model, where everything flows through the Control Tower, gives you a controlled, auditable path for images to reach your edge.

Zero configuration registry at edge sites

The site registry is embedded in the Edge Enforcer. There’s no separate component to install, no configuration to manage, no additional resource overhead. When you onboard a site, the registry is just there, ready to receive images as soon as you deploy an application.

Concluding thoughts

The image registry isn’t the most glamorous part of a container platform. In cloud environments, it mostly stays out of your way. But at the edge, with unreliable connections, constrained resources, and potentially hundreds of sites, image distribution can quietly become a real operational challenge.

Now that you know a bit more about how images and registries work, here’s the good news: with the Avassa Edge Platform, you can forget most of it. The registry is built into the platform at both ends, in the Control Tower centrally and in the Edge Enforcer at each site. Images flow automatically to where they’re needed when you deploy an application. They’re replicated locally for resilience, pinned by digest for consistency, and cleaned up when no longer needed. There’s nothing to install, nothing to configure, and nothing to manage at the sites.

It’s just there, and it works. Which is exactly how infrastructure should be.