Top 5 most common confusions from our first 5 years in edge computing

During the five years of Avassa, we have had many hundreds of conversations on the broad topic of edge computing. Ranging from focused commercial negotiations to friendly chatter over coffee at events. Literally hours and hours talking about computing in the distributed domain and the finer points of it. With a lot of time spent on a singular(ish) topic, we have observed some of the inevitable and entertaining confusions specific to this domain.

Therefore, we are proud to present to you, directly from our private stash, the five most common points of confusion around edge computing.

When you say edge, which edge is that?

While “the edge of the network” gives a fairly definitive portrayal of where applications are running when they are running “at the edge,” reality is rarely as straightforward. Defining the “edge” in edge computing remains one of the unsolved confusions of this category (or at least one that takes a few words to explain). Anything from a handheld Android device to a regional data center can at times be claimed as “the edge”. That said, things are much clearer now than they were only a couple of years ago, largely thanks to the categories of edge that are taking shape.

As providers of purpose-built tooling for managing and operating edge applications, staying aligned with our users on the definition of edge has been key. In the context of the regional edge, such as a hyperscaler availability zone, managing container applications is already a solved problem, just like in the central cloud. Meanwhile, at the IoT device edge, the need for multiple workloads sharing common infrastructure, automated deployments, and high feature velocity is usually not part of the requirements. But, in the layer between, the on-site edge, users need compute. Compute that is heavy enough to support multiple workloads and Edge AI initiatives, yet small enough in footprint and autonomous enough that cloud tooling won’t do the trick. Here, edge-specific tooling becomes the necessary bridge between data sources and the cloud.

So here we are, firmly planted between your Garmin sports watch and a regional hyperscaler data center. Solving problems specific to that edge.

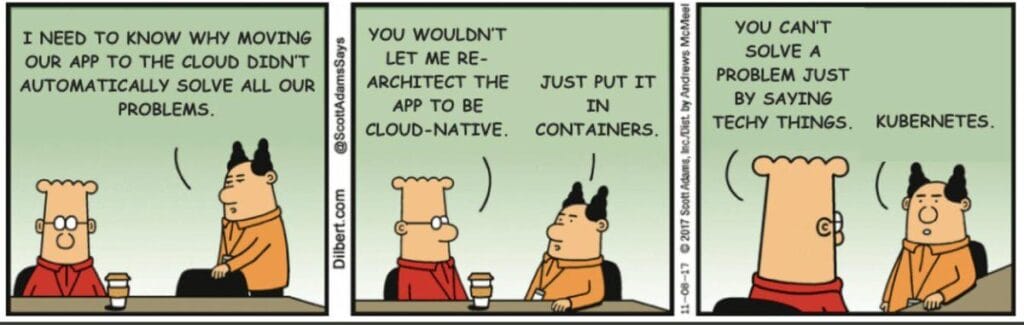

Containers != Kubernetes

Our industry has a history full of technologies that managed to break out from their initial place and into mainstream culture. I mean, any technology that is a punchline in a Dilbert strip clearly has something going for it. The closest example we know of is Enterprise JavaBeans (EJB) and J2EE, that built on Java’s early success in server-side apps. This led to the creation of the EJB standard within J2EE, promising a component model for distributed enterprise systems. Companies assumed “enterprise” meant “we must use EJB.” It became the default dogma even when a lightweight servlet or PHP app would have sufficed. But simpler frameworks (Spring and later microservices) evolved precisely to escape this over-engineering.

A similar pattern can be observed in our domain. We solve managing containerized workloads at the edge, and we are well-known for not needing Kubernetes. So the last five years have been chock full of conversations where we have needed to explain the absence of something, rather than the actual architecture at hand. But just like with EJB and J2EE, we see a clear anecdata-driven trend towards simpler frameworks for running containers at the edge. In this case, back to slimmed-down and purpose-built container runtime environments running on immutable operating systems.

Less time spent on the infrastructure, way more time spent on developing, deploying, and managing containerized applications.

Latency, enterprises can deal with. Downtime, they can’t.

When we founded Avassa, much of the perceived value was based on the need for certain applications requiring low-latency response times. But it quickly became clear to us that the difference in latency between “near-cloud region” and a dense micro-edge node had marginal importance.

So while latency remains one of the drivers for placing application workloads at the distributed edge (let’s say, in the middle of a top 10 list), what clearly has proven itself to be one of the biggest, if not the biggest driver, is the non-acceptance of application downtime. Or, what we like to call offline capabilities. We hear this when we’re talking to a retailer who no longer allows for interrupted sales in the store when a cloud-POS is down. We also hear it from machine builders who need to allow their autonomous self-driving agricultural robots to run down the fields, including that creek where connectivity is shaky. In both examples, offline capabilities are the answer.

And hard pass on downtime has caught up to (and passed) latency as the more common and valued driver for pursuing an edge computing project.

Telco started strong, but won’t win the race to the edge

A few years back, much of the buzz around edge computing was focused on the concept of Multi-access Edge Computing (MEC). This architecture assumes that edge computing would largely happen at the edge of cellular networks managed by the communication service provider. It conflated two ideas.

The first idea was, as mentioned above, that faster response times would be the main driver for shifting applications to the edge. But as we’ve learned, offline capabilities trump it all.

The second idea was that since mobile service providers own distributed real estate, they would be the obvious entities to host and manage the edge infrastructure. Turns out that the locality requirements, in combination with the lack of enterprise sales capabilities among the telcos, effectively killed off the whole concept. Despite various attempts to marry private 5G with on-prem deployments, we have not seen these types of deployments develop into a durable enterprise.

What is happening is that enterprises with a distinct business drive to host applications at their on-prem edge are drawing on their experiences from the cloud to build edge infrastructure that is as easy to use and deeply automated as their cloud footprint.

We’re cool, but not that kind of cool

We’ve had a couple of show-floor walk-ins at Edge Computing events asking if we can help them with temperature-regulated transportation of pharmaceutical goods across the Atlantic.

Not as far-fetched as one might think, given that we’re both a container orchestration company and a Gartner Cool Vendor. Containers, cool, cool containers. And you can’t blame a champ for trying to parse a booth backdrop, right?

After explaining that our containers are software containers that don’t need industrial-grade air conditioning, just automated orchestration and a bit of compute to keep workloads humming at the edge, we usually laugh about it.

It’s an amusing mix-up that says a lot about the horizontal nature of the industry, where edge computing is growing across a diverse set of industries, and sits at the intersection of physical infrastructure and modern software delivery. We just happen to build for the latter, orchestrating software containers, not refrigerated ones.

Keep reading: Edge Computing: 5 Years of Navigating a Category In the Making